Franz Erhard Walther, born in Fulda (Germany) in 1939, has since the 1950s been developing work that examines the role of spectators in the grasping of a piece, and also its status. As the creator of the famous 1-Werksatz (First Work Set) which is made up of 58 objects to be put into motion, he has turned public participation into one of the drivers of his art.

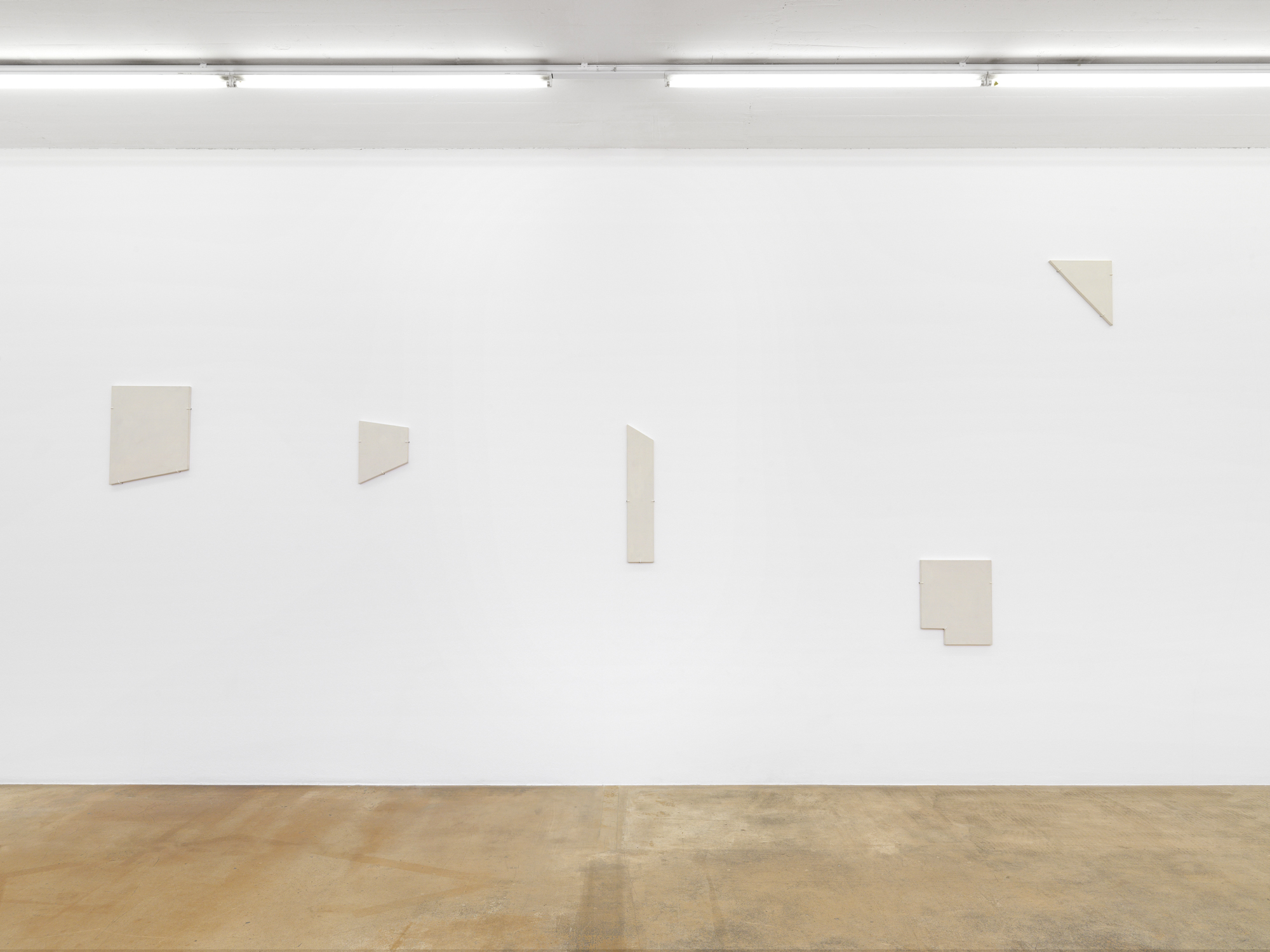

Fünf Nesselüberklebte Holzplatten. Unmassformen (1963), a five-part mural work, is contemporaneous with the birth of Werksatz (1963-1969), a period during which Walther was still a student at the Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf. There can already be found here his essential choice of materials, with the covering the of five panels by fabric which, as of 1963, was to become the actual material of all the objects in First Work Set. Thanks to this new material for painting and sculpture, the artist took a step forwards in terms of the classic use of matter, which also implied a change of procedure: sewing was now to become his sole production technique.

Fünf Nesselüberklebte Holzplatten. Unmassformen can be displayed on a wall according to a variable geometry. While it is still part of the pictorial world, given its relationship with hanging, this piece, which is run through with emptiness, also greaves over such concerns in at least two ways: when it comes to the image, or the wholeness of a picture, of which only spaces, fragments, or leftovers are presented. Such pictorial bereavement is also graphic, given that the practice of drawing was a foundation point for Walther: the three fabric ribbons, which come down from the wall and which make up Drei Bänder (1963), are lines outside the page which bring into their identity the artist’s material conversion, which is fundamental for him. And which, just like the five mural panels, embody a proto minimalism.

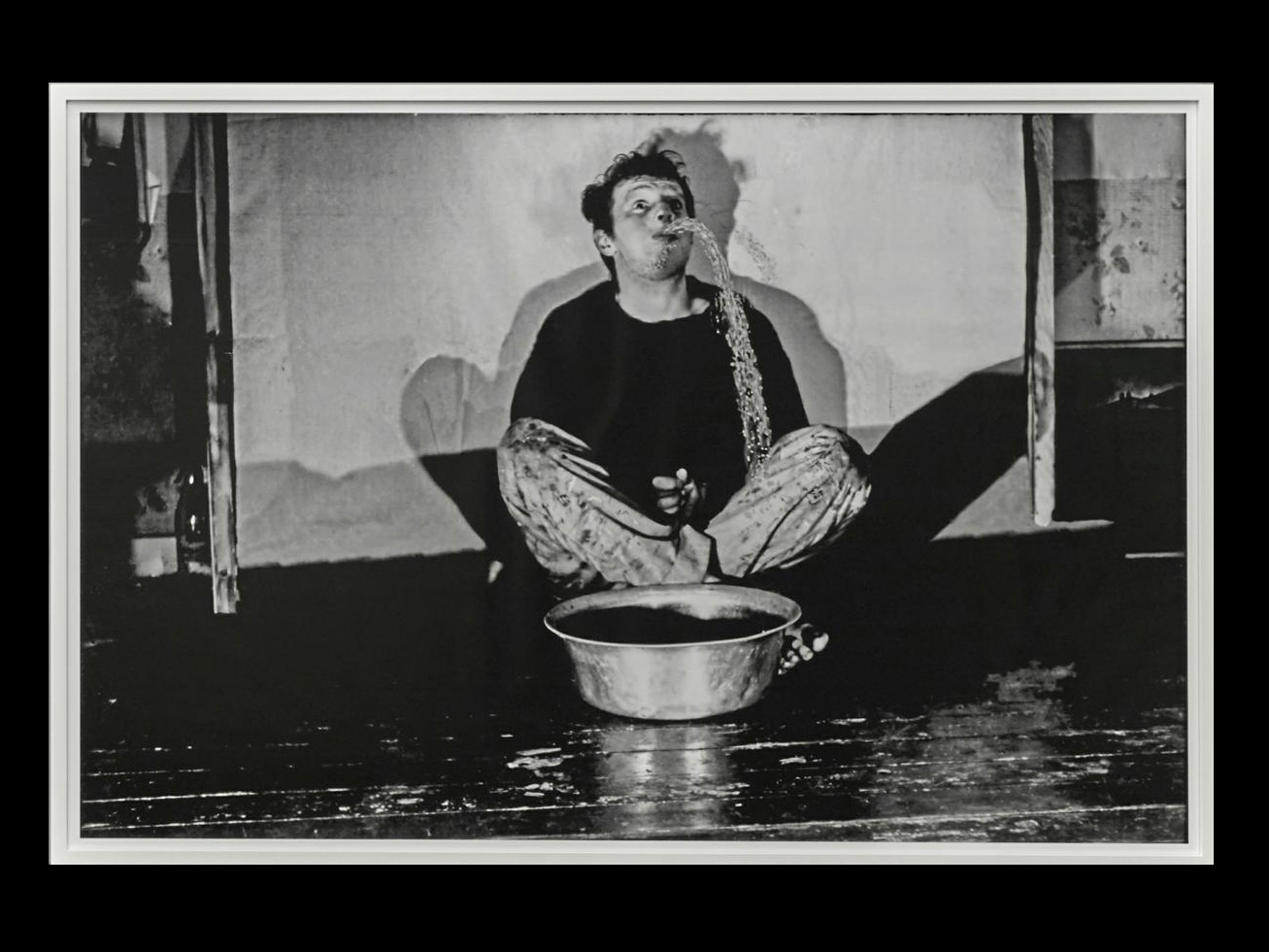

More recently, Skulptur und Bild nicht zu trennen (1986) is a mural set-up that reaches out towards the spectator. As opposed to the two pieces from 1963, colour, which is a highly important factor in Walther’s work, is clearly present, his choice always being a carefully personal one. While being neither really a painting, nor a sculpture strictly speaking, this vertical arrangement, going with the human stature, can integrate an artist. He or she can then activate it in at least two ways: by standing up in one of the two alcoves, and by putting on the cotton jacket hung on one of the panels to their right. He or she is then wearing the same colour and is transformed into a part of the piece. Their actions (Handlung), which here come down neither to a real performance nor a happening, allow them to spread out the meaning and outreach of the piece by becoming embodied as a site and a tool for the work. In this way, Walther has deeply renewed the framework of art and greatly anticipated, as early as 1963, the relational practices that would occupy the artistic limelight many years later.

De l’origine de la sculpture (1958–2009)

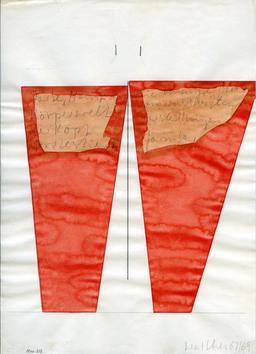

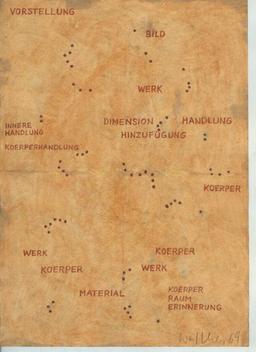

Wortbilder–Wordworks, 1957–1958

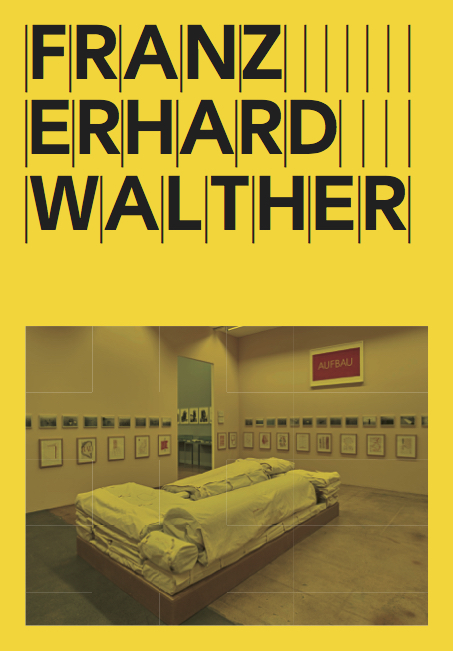

Werksatz 1, 1963-1969