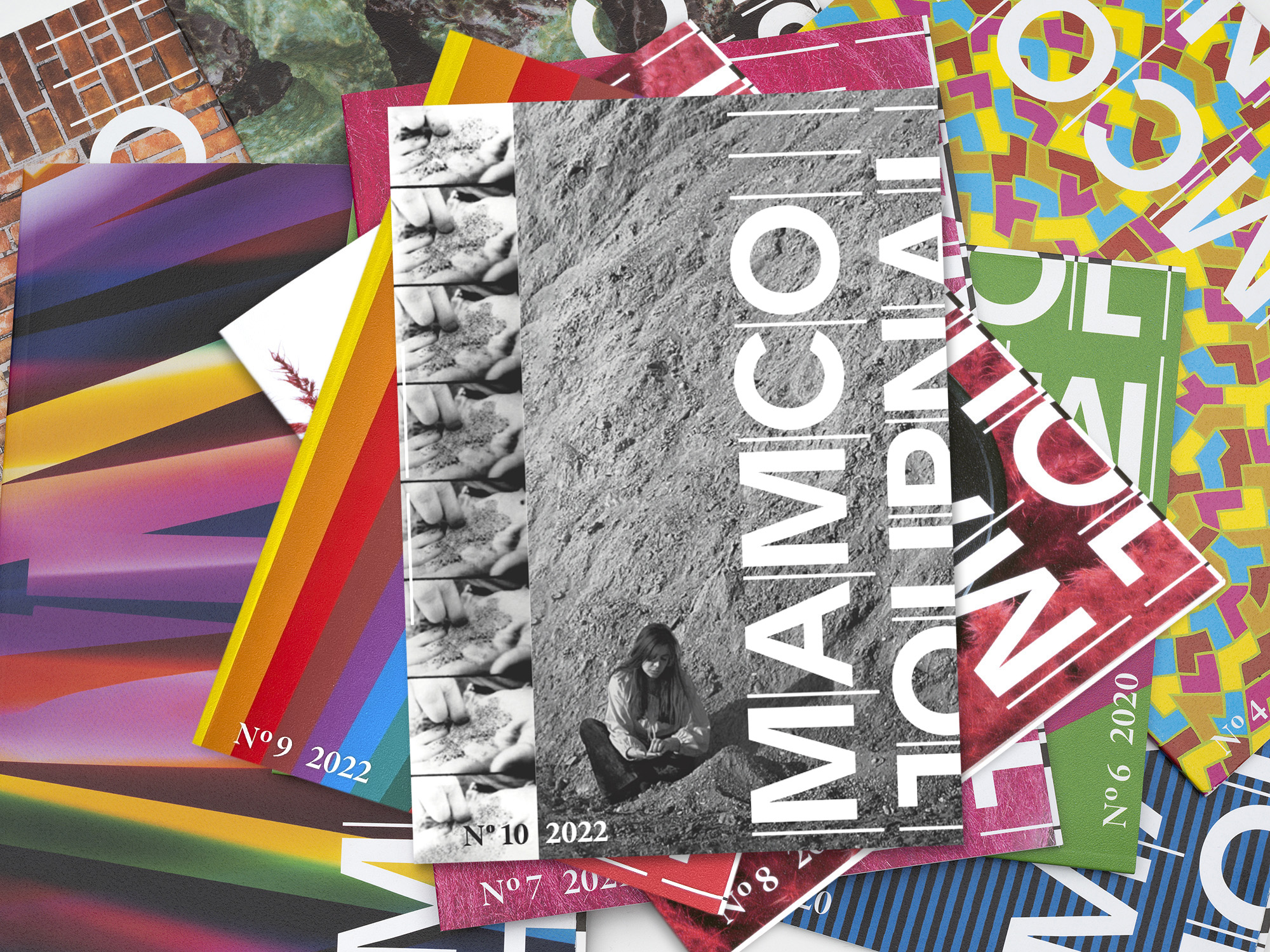

MAMCO Journal

MAMCO provides a narrative, extended over a fairly short period (from the 1960s to now), so as to give back an historical syntax to the works it presents. For each sequence, there is a corresponding issue or theoretical question which the museum, as a laboratory for the collective writing of history, aims to explore and then reveal to the public the current state of its research. MAMCO Journal aims at presenting the topics we have selected through the year, the concepts that were elaborated during the preparation of the exhibitions, and the results that have (or have not) been presented to the public. It is published twice a year and is available here in a PDF format to download. To freely receive the printed version, please contact c.gouedard(at)mamco.ch.

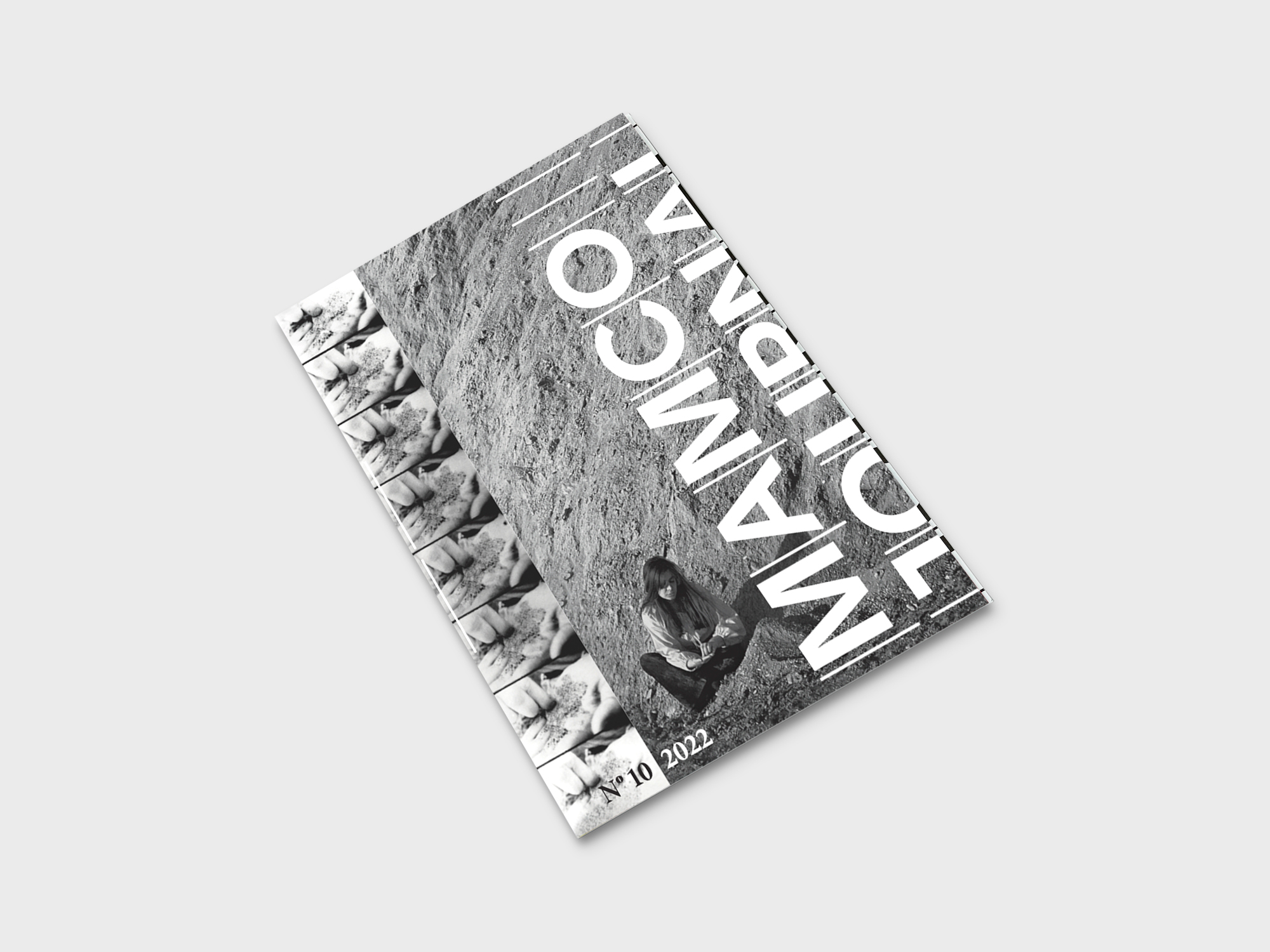

N°10

In 1965, British science-fiction author Brian Aldiss published Earthworks, a dystopian novel set in a world of environmental catastrophe and extreme socioeconomic inequality where the population lives under a police state, where wealthy “Farmers” run rural labor camps, and where “Travellers” who have broken free of social controls are ruthlessly hunted down. Two years later, the artist Robert Smithson embarked on a trip through the post-industrial landscape of New Jersey, reading Earthworks on a bus to Passaic. The fact that Smithson referenced the title of Aldiss’ novel prominently in one of his publications emphasizes the extent to which the artist’s work—infused with his ideas on entropy and his rejection of modernism—sets up a new kind of relationship with the environment, with history, and with time.

In 1968, the Dwan Gallery in New York hosted a show entitled Earthworks, which featured pieces by Smithson (who was one of the minds behind the event) alongside a number of other artists: Carl Andre, Herbert Bayer, Walter De Maria, Michael Heizer, Stephen Kaltenbach, Sol LeWitt, Claes Oldenburg, and Dennis Oppenheim. This exhibition marked the first formal recognition among art critics of what would come to be known as Land art. The Earth Art exhibition, organized the following year by Willoughby Sharp at Cornell University, was another example of an emerging trend that saw Minimalist, Conceptual, performance, and Body artists thrown together under the same banner. They were a new generation for whom art was to be created with and within the landscape.

This banner covered artists with very different—even opposing—sensitivities, from Hamish Fulton and Richard Long, who seemingly sought to revive the “picturesque” tradition of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, to Michael Heizer and Robert Morris, who chose deserts and landscapes wrecked by human activity as the backdrop for their interventions.

As if presaging Spiral Jetty, Smithson’s famous creation on the shore of the Great Salt Lake in Utah in April 1970, Laura Grisi’s film The Measuring of Time (1969) portrays her counting grains of sand on a beach as the camera moves around her in a spiral motion. And while Smithson set up a dialectic between his outdoor interventions (“sites”) and the pieces he showed in art venues (“non-sites”), Grisi’s works in the late 1960s simulated natural phenomena such as fog, wind, and rain in galleries.

Grisi’s desire to “reinvent” nature in exhibition spaces bears many similarities to the Ricostruzione della natura (Reconstruction of Nature) series by Pino Pascali, who is often associated with the Arte Povera movement. Around the same period, Piero Gilardi was making his first Tappeto-Natura (Nature Carpet) pieces: cut and painted polyurethane rugs that depict fragments of nature.

Other artists had more overtly political aims. For instance, Judy Chicago’s Atmospheres—a series of videos featuring naked women and colored smoke in natural settings—were, according to the artist herself, “intended to transform and soften the landscape, introducing a feminine impulse into the environment.”

Through their respective forms of expression, these artists adopted a fresh approach, breaking from the joyful exuberance of Pop art and the celebration of consumer society that had prevailed just a few years earlier. And they signaled the emergence of a new generation with “environmentalist” sensibilities.

While concepts such as “biosphere” and “ecosystem” have been around since before the Second World War, the publication of the 1972 report Limits to Growth, commissioned by the Club of Rome and prepared by Dennis Meadows, sparked a dawning realization of the effects of human activity on the planet. From that point onward, the dangers of the Anthropocene (the geological age corresponding to the appearance of humans on Earth and their impact on the planet’s ecosystems) have been widely acknowledged, although individual and political responses remain extremely piecemeal and uneven.

The summer of 2022 will surely go down in history as the point at which climate-related fears became embedded in people’s minds and in the media discourse. It could be argued, however, that artists (and science-fiction authors) started the grieving process for our changing environment some 50 years ago—accepting the loss, symbolically circumscribing it, and attempting to rebuild in its wake.

Eté 2022

Our summer exhibition program is conceived as an innovative modus operandi . Based on the concept of an annual “rendez-vous,” borrowed from the world of magazines or biennales, the aim is to bring together diverse practices connected in apparence by nothing but the fascination they exert on us.

Around the artists invited this year— Douglas Abdell, Stéphanie Cherpin, Jeremy Deller, Calla Henkel & Max Pitegoff, Tobias Kaspar, Seob Kim, and Julia Wachtel—talks, performances, and events are programmed throughout the summer (see the last page of this publication). Open from Thursday to Sunday, the museum also sets itself on summer time, welcoming you from 5 to 10 pm, after work ... or sun, on free access. été 2022 represents a new way of thinking about our collection (and how it grows, is exhibited, and communicated), a chance to experiment with the concept of the museum as a place of “experiences,” and to re-think ways to showcase new talent, support and collaborate with artists across a broader timescale than that of the “simple” exhibition.

It is of course no accident that this new work method coincides with our planned renovation of the MAMCO building, in association with the City of Geneva: we are preparing for the future by redefining and experimenting with the future outlines of the museum, once it will have secured the setting and means it deserves.

N°9

Now that an ambitious renovation plan has been selected, MAMCO is moving on to the next stage in its development. We will use the next few years before construction begins to make detailed projections for features and functions that are currently missing from the museum and its building, such as a gathering space, outreach facilities, and galleries to display large-scale works and free exhibitions.

We also plan to reflect together on current issues in the museum world. After all, museums today are under pressure not only from those who would enlist them in their cultural battles or turn them into cultural commodities, but also from techno-utopians who see digitalization as the solution to all future challenges.

But first and foremost, we want to take advantage of this transformation to reaffirm MAMCO as a museum of contemporary and modern art. For us, it is no longer a question of showing what contemporary art owes to modernism so much as what modernism can teach us about contemporary art.

We must not forget that before museums started struggling to compete with entertainment figures—or, according to the ICOM’s failed attempt at redefinition in 2019, to become “democratizing, inclusive, and polyphonic spaces”—they were places of learning. In that sense, museums have more in common with universities and laboratories than with the entertainment and tourism industry, although they provide knowledge to the public without speaking down to them or discriminating based on academic status. Rather than encouraging visitors to interact or participate in some form of simulation, museums promote a form of agency by providing visitors not only with the results of research but its context and tools, in complete transparency.

History has two enemies: amnesia (along with its politically weaponized form, populism) and fetishization of the past. After all, the study of history can reveal narratives that make market simplifications and the establishment of a canon untenable. Those are precisely the types of narratives to which we intend to contribute. This season’s contributions spring from two different starting points but converge upon a formative modernist motif, as identified by Rosalind Krauss in 1979—the grid.

First, the Verena Loewensberg retrospective and Geraldo de Barros exhibition reveal how a modern vocabulary established in the early 20th century postulated the creation of a universal language akin to science and music that could be applied to all forms of creation.

Second, exhibitions of post-minimalist works from the 1960s by Jackie Winsor and Jo Baer show how, like many other women artists, they worked with geometric forms and repetition to develop their own practice by making use of a “rectilinear framework primarily to contradict it,” as Lucy Lippard observed.

This convergence upon a system of geometric coordinates originating in the rational principles central to Western thought would prove to be a launchpad for radical shifts, liberations, ruptures, and deviations—all in all, a fairly good definition of the artistic practices of today. By exploring and challenging the grid, these artists invite us to do the same in all disciplines where it appears, be it in the form of graphs, tables, or programs that are taken to be undisputable facts when they should be seen as interpretive frameworks.